Here is the second installment of my 2005 senior thesis on Catholic kingship that I began posting last week. Thanks for the feedback so far! (

Click here for part 1).

I do know that all of these chapters will suffer from being too broad; being that I was somewhat limited by time and length, and I was not able to develop them as much as I would have wanted. This is perhaps most true in today's post, which is the most speculative and theoretical chapter of the work and probably the easiest to find gaps and holes in the argument. I basically make the case that the east had its own tradition of authority and the west its own distinct way of viewing authority. In the antique world, these traditions were opposed to each other. But in Christianity, which was born of Asia but became European, the eastern and western traditions are fused together successfully - the result is the Catholic monarch, who is certainly not an eastern despot but is also far removed from the republican-democratic traditions of Greece and Rome.

I look forward to your feedback. Footnotes can be found at the end of the post, which I recommend you browse also because they have some interesting supplemental information.

Chapter One: Two Traditions of Power

In the European political tradition, two ideologies of power have been predominant; namely, that of the west (the Greco-Roman, and later Germanic, traditions) and those influenced by the east (the Mesopotamian-Egyptian model). In the western tradition, power comes up from below, from the people. In the Greco-Roman civilizations, this power is vested in any number of assemblies or magistrates; in the Germanic cultures, it is vested in the tribal assembly or warrior band. By contrast, power in the eastern model is seen as descending from above, coming down from the gods and being bestowed on a single individual, be he a pharaoh, Persian king or just some local priest-king of a city-state. This conception of power held true even in the Far East, where the Emperor of China was also the “Son of Heaven.” In Christianity, a unique union of these two ideals of authority arises. Coming out of the Middle East as it did, it possessed by its nature an eastern and autocratic ideal of kingship. However, when it took hold in the Roman west and amongst the German tribes, the classical and Germanic tribal ideals of kingship entered as well, blending with the eastern ideas. The result was the Christian monarchy of the Middle Ages. The following sections may seem like a digression, but an understanding of them is essential in order to understand where the Christian monarch of the Middle Ages got his ideas of kingship.

Eastern Models

In the civilizations of the Fertile Crescent, the prevailing view of authority was that it was a divine right that was given from above. The ruling monarch was chosen by the gods for the task of kingship; if he was part of a dynastic government, then he was chosen even from birth for lordship. The authority was vested in the very person of the king, not just in his office. An example of this is the Egyptian Pharaoh. In the Old Kingdom, the very person of the Pharaoh was believed to be the incarnation of Horus on earth (later in the Middle Kingdom, it was modified and the Pharaoh became the son of Re and mediator between men and the sun god).1

This idea of authority being vested in the person and not just the office is a crucial distinction between the eastern and western models. The fact that the authority was vested in the person himself meant that it gave divine sanction to the ruling monarch’s whims, which tended to give authority in the Middle East a very arbitrary character. A king might command anything, no matter how cruel or mad, and expect the submission of his subjects. Mesopotamian scholar Jean Bottero comments on the relationship between the king and subjects in the ancient Near East:

"Subjects had no other purpose in life than to obey their king and his representatives, and to provide those rulers, through their constant labor, with what they needed to lead an opulent and leisurely life, free of all worries and thus free to govern their people with a view to their prosperity."2

The structure was that of a social pyramid, with the monarch at the top vested with supreme authority sanctioned by the divinities of the city-state (Mesopotamia) or centralized nation (Egypt). Everybody else existed in the pyramid to obey and serve him. Given this view, it is not surprising that pyramids and ziggurats, which seemed to typify this social system, were first devised in such cultures.

This arbitrary nature of authority in the eastern model is evident in many examples from antiquity. A well known story from Persia is the account of King Xerxes ordering his men to give the Hellespont three hundred lashes as punishment for a storm which destroyed his bridge across the channel. “You bitter water,” he cursed the strait, “your lord lays on you this punishment because you have wronged him without a cause…for you are of a truth a treacherous and unsavory river.”3 Evidently, this Persian monarch considered himself not only King of Perisa, but lord over nature as well. The Median King Astyages is said to have killed and cooked the son of one of his officers, Harpagus, and served the stewed boy to his own father for dinner. When Harpagus realized what the king had done, he merely bowed and said, “Whatever the king did must be right.”4 The Biblical stories of the Babylonian and Persian periods further attest to the arbitrary nature of authority as well as the exalted idea of the ruler in the ancient Middle East. King Nebuchadnezzar ordering all his subjects to worship a golden image on pain of death, Darius’ interdict forbidding prayer to any god but himself, and King Ahasuerus of Persia’s law punishing with death anybody who entered his court unbidden are all examples.5 “The king,” says Bottero, “was…all powerful in the land…he was capable, on a whim, of reducing them [his subjects] to nothing, or of heaping good things upon them, provided he was moved enough through offerings, ostentation, and requests.”6

This divine authority wielded by the Middle Eastern monarch should not be conceived as being some kind of tyranny imposed on an unwilling populace from above, though the ancient Middle Eastern monarch certainly had the power to tyrannize his people if he wanted; rather, it was a system that the people themselves assented to and adhered to rigorously. The response of Harpagus to King Astyages of Media is a telling example of how the average person viewed royal authority. On the sadistic murder of his son, he only responds, “Whatever the king did must be right.” The Middle Eastern monarch did not have to impose his authority on the people tyrannically as someone like Caligula or Commodus did, because the cultural mentality of Middle Eastern culture rendered the populace more than willing to accede to his authority voluntarily. There was very little dividing the gods from the king, and a king who won renown by performing great deeds could be assured not only of the homage of his subjects, but of their adoration and worship.7

While looking at eastern models, the ideology of kingship in ancient Israel is worth studying in some depth since it contributes so much to later Christian views of kingship and authority. The system of kingship takes on a peculiar form in ancient Israel because of its monotheistic faith. The ancient Israelites would never make the mistake of equating their temporal king with a god, for there was only one God who was so far beyond mere mortals that any equation of Him with even the greatest of kings was a terrible blasphemy. Nor would the Israelites, with their strict moral code, approve of the idea that “whatever the king did must be right.” Israelite kings were expected to fulfill strict moral obligations; if they did not, they were censured by the scribes and prophets.8

That is not to say, however, that the Israelite conception of kingship was fundamentally different from the Persian, Mesopotamian or Egyptian views. Royal authority was still something supernatural that descended upon the king from above. The Scriptures are replete with such examples of this ideal of sacral kingship. Right from the first time Israelite kings are mentioned, in the Mosaic code, the king is presented as someone “whom the Lord your God will choose.”9 The exemplar of biblical kingship is found in the stories of David and Solomon in the books of Samuel and I Kings. These exemplars can be contrasted with the biblical type of the wicked king, Saul, who reigns just prior to David.

In all cases, kingship is conferred upon the would-be monarch by the act of anointing with oil. This symbolizes that the king has been chosen by God; the oil, administered by a prophet (later a priest) is a type of sacramental sign that symbolizes the Spirit of God resting upon the king. This is a mixed blessing: it at the same time gives the king sacral-royal power to rule with authority given from God and also binds the king to strictly obey the precepts of kingship set down by God. Blessings follow if the king is pious and obedient to the Lord; if not, curses befall the kingdom and it is torn from the hand of the rebellious monarch.

The biblical perspective on kingship is clearly in line with the other prevailing models of the ancient Middle East in its emphasis on the king being chosen from above. Consider the stories of Saul and David. Saul is the king who is tall, strong and handsome, the natural choice of the people. Thus when the people clamor for a king in I Samuel 8, Saul is a natural choice. Yet the Scriptures seem to condemn the selection of this first king of Israel. The motion of the people for a king is presented as a rejection of God’s lordship. God tells Samuel, “Hearken to the voice of the people in all that they say to you; for they have not rejected you, but have rejected me from being king over them.”10 Nevertheless, God accepts the “democratic” will of the people and gives them Saul to be their first king.

By contrast, David, the man after God’s own heart, is the complete opposite of Saul. Unlike Saul, he is small, weak and unimpressive. He is not at all a king that would be chosen by popular vote; even Samuel fails to recognize David and instead believes that one of his older, larger brothers is the Lord’s chosen.11 David is in every way a man chosen not by human wisdom but by God and receives a different kind of authority than Saul. While Saul is rejected by God as soon as he sins ( I Sam. 15), David is promised by God that He will establish his house forever and will never cease to provide an heir from David’s line ( II Sam. 7), even though David committed a greater sin in the Uriah affair than Saul had by not destroying some Amalekite cattle! The nature of their kingships is different. A close inspection of the anointing narrative of each king reveals this. Saul is anointed with a vial, a man-made object, while David is anointed with a horn.12 This seems to indicate that Saul’s authority, symbolically portrayed by his anointing, was given him by man; hence, the vial, a man-made object. This is born out by Saul’s own testimony. When he sins and is confronted by Samuel, his excuse is that “I have transgressed the commandment of the Lord and your words, because I feared the people and obeyed their voice.”13 On the other hand, David is anointed by a ram’s horn, something not man-made, which seems to indicate that his kingship is entirely from God and not due in any part to human consensus.

One theme that is constant throughout the chronicles of the Israelite kings is the idea of rewards and punishments. If a king is pious and obedient, like David, he can expect temporal blessings from God: security at home, influence abroad, wealth, healthy heirs and the destruction of enemies. However, if the king is faithless, like Saul, then he can expect curses: internal rebellions, defeats at the hands of foreigners and the premature death of his heirs, leading subsequently to the end of his house. When Samuel confronts Saul for his disobedience, he tells him, “Because you have rejected the word of the Lord, he has rejected you from being king…The Lord has torn the kingdom of Israel from you this day.” 14 This connection between sin and the collapse of the kingdom is reiterated again and again throughout the Scriptures. Later, in the book of I Kings, God tells Solomon, “Since …you have not kept my covenant and my statutes which I have commanded you, I will surely tear the kingdom from you…”15 It is in the person of Solomon that the blessings and curses of sacral kingship are seen most clearly, for he is both extraordinarily faithful and very wicked during his long reign. On the one hand, his virtues set the bar for all future Christian kings from Constantine to Charlemagne and Alfred. He excels in wisdom, is well versed in God’s word, builds the holy Temple of Jerusalem and receives honor and tribute from foreign nations. On the other hand, he burdens his people with harsh taxes, sacrifices to foreign gods and greatly multiplies both his wealth and his harem.16 In these vices he is the type of the good king gone bad and receives from God the punishment due to an unfaithful king: the “tearing” of the kingdom out of his hand.

The king receives a mighty grace from God. The Book of Proverbs goes so far as to say that the decisions of the king are “inspired” by God.17 The Book of Ecclesiastes warns that it is wrong to wish the king harm, “even in your thought.”18 Because the king receives such great graces from God, it is especially heinous when he turns to wickedness, like Solomon. Essential to Israelite (and all ancient Middle Eastern) political thought is that the fate of the nation is bound up with the person of the king. If the king is very wicked, he curses not only himself but brings his curse upon the entire nation. When Manasseh sacrificed his children to the pagan god Moloch, God was so outraged that even the righteous reforms of King Josiah were unable to dissuade the Lord from punishing Israel, and the Babylonian Captivity resulted, which the Scriptures explicitly affirm was the punishment for the sins of Manasseh.19

So, to sum up the eastern models of kingship: First, the authority to reign comes from the gods/God, down from heaven and rests upon the monarch. This ideal is sacramentalized in several cultures by the act of anointing, whereby the king is symbolically chosen by the gods and given their authority to rule in their name. Secondly, this authority rests with the person of the king (not just his office), which authorizes and potentially “divinizes” every act of his will as a sacred and royal command.20 Thirdly, because of this emphasis on sacred kingship, any authority coming from popular consensus is suspect. The people are simply an “undifferentiated mass”21 who cannot be trusted. King Saul explains his sin by saying, “I feared the people and obeyed their voice.” The prevalent social structure was that of a pyramid with the king supreme at the top supported by an “inchoate mass of subjects”22 whose job it was to support him and his bureaucracy. This is not an active act of tyranny on the part of the monarch, but a system found in the east from time immemorial and bound up with Middle Eastern cultural tradition. Finally, a just and pious king can be expected to receive temporal blessings of the gods upon his realm and (in some cultures) deification after death. The wicked king can expect his kingdom to suffer. This is the idea of rewards and punishments, in which the fate of the nation is inextricably bound up with the king. In Babylon, Egypt and Persia, a king’s “goodness” is his legal equity and his piety to the state gods; in ancient Israel, it is his morality and adherence to Mosaic law.

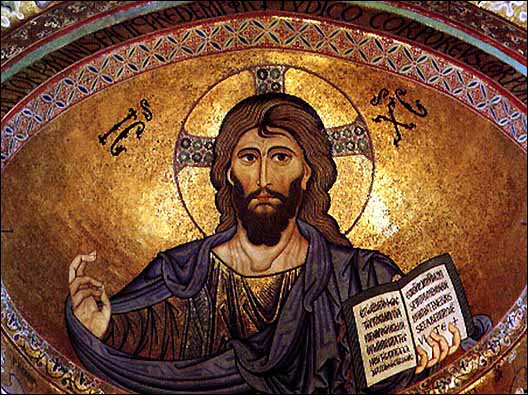

Christian kings, seeing themselves in light of Old Testament kings like David and Solomon, will pick up several of these ideas. There will be a particular emphasis towards the eastern model in the reigns of the earliest Christian monarchs, the Emperors of Byzantium. Later, western kings will adopt a version of kingship that was more of a mixture between the eastern models and the Greco-Roman model, which will be examined in the next section.

Western Models

Ideas about government and authority were drastically different in the west, in those lands lying west of the Bosphorus. In antiquity this region was shaped by Greco-Roman civilization and it is to the governments of Greece and Rome that we must now turn.

The Greco-Roman ideology of power sees authority not as something that primarily comes down from heaven as a gift of the gods to the person of the monarch, but as something that comes up from the consensus of the people and is vested in an office, not a person. An example of this is the Roman legend of the patriot Cincinnatus. Called from his farm to help save a beleaguered Roman army, he accepted the authority of the dictatorship, saved the army and routed the enemy, then promptly resigned his dictatorship to return to his plow. This popular, though legendary, example demonstrates how the power was vested in the office of the dictator, never in the individual person.

This power is given by the assent of the state and the gods are called upon by the people to bear witness to the authority wielded by the magistrate. In the previous section, the model of the pyramid or ziggurat was proposed as an analogy to the Mesopotamian/Egyptian style of government. In the west, a more fitting model is the Greek temple. The structure is composed of several columns, each equally bearing the weight of the roof. Again, it is fitting that a structure such as the Greek temple should have emerged amongst a people who viewed authority as something coming up from below, granted to the magistrate by the public.

The Greeks and Romans alike found a distaste for kingship early on. Many of the Greek city-states were ruled by tyrants, such as Pisistratus of Athens or Pheidon of Argos who were different from kings only in name, until the 6th century BC when they began to be overthrown and driven out by a series of popular revolutions. After this, the Greek city-states began to adopt the democratic governments that the classical age is remembered for. This advent of democracy was especially powerful in Athens. In Rome, according to tradition and some scant archaeological evidence, a dynasty of Etruscan kings was overthrown sometime around 509 B.C. and replaced by the Republican form of government that Rome operated under successfully for almost five hundred years. The experience of Greece under the tyrants and Rome under the Etruscans bred a hearty dislike of the idea of power being vested solely in one individual.

The very names that the Greeks and Romans chose for their governments emphasizes how different their view of the state was from those views in the east. In Greek, demokratia means “power of the people.” Likewise, the Latin phrase for Republic, res publica, can be literally translated to mean “the public thing” or the “thing of the public.” In both cases, it the people who are seen to be the foundation of the authority of the state.

On some levels, it is uncertain how the Greeks and Romans came to these forms of government. The historical acts and political drama behind their developments is clearly visible, but where these peoples got their political ideology from is uncertain. It is easy to see the laws of Solon, the administration of Pericles, the Sexto-Licinian Compromise and the publishing of the Twelve Tables and to attribute the development of Greco-Roman popular governments to such acts, but it is difficult to say where the Greeks and Romans first developed their penchant for representative government was behind these acts of legislation and assumed by them. The easiest answer, but also the most dissatisfying from a historic viewpoint, is that the Greeks and Romans had an innate sense of justice and law that they manifested in their social and political structures. Historian of antiquity Michael Grant seems to adopt this view and says of the early Romans:

"It is impressive that a people at such a relatively early stage of development were so clearly able to disentangle law from religion, deriving the sanction of their legal pronouncements not from any divine or wholly or partly legendary lawgiver, as so many of their predecessors in other places had done, but from a sense of justice and equality, still narrow, yet already strong."23

Both cultures placed high value in social justice and in the moral quality of the individual, especially of the magistrate. The Greeks prized a virtue they called arête, which originally meant “warrior prowess” but came to be understood in terms of diplomatic excellence exercised in any of the many public assemblies that dotted ancient Greece. Likewise, the Romans valued virtus. Like arête, virtus was originally a war term and meant “manliness.” But in time it came to have a broader application and can be rendered accurately as “virtue” by middle-Republican times and denoted excellence in both war and government. These characteristics were seen by the Greeks and Romans as essential to any magistrate. If a government was to be by the people, then the people had to be good people.24

With such ideas, acts of the Greeks and Romans were always viewed communally. It was never an individual alone who acted, but the community who acted out its will through the agency of the individual. Herodotus and Thucydides recount in their writings the very public nature of Greek government. In the Persian War (Herodotus) and the Peloponnesian War (Thucydides), whether or not to go to war or make an alliance was decided by furious debate in the assembly hall, after which a vote was taken. Even military matters, such as where to move a fleet or when to attack were put to a vote amongst military commanders. Any act of authority had to be sanctioned by the citizenry. Thus, “acts of state were attributed not to a personified polis but to the community-for example, not to Thera but to “the Thereans,” not to Sybaris but to “the Sybarites,” The emphasis is on the plurality.”25 In Rome, likewise, official acts are and monuments are sanctioned by the Senatus Populusque Romanus, “The Senate and the Roman People.”

The will of the people was expressed in any number of assemblies in the Greco-Roman world. Athens had its Council of 500 and its older Areopagus Council, while Rome had the Curial Assembly, the Centurial Assembly, the Council of the Plebs and of course, the Senate. Though membership in these councils was restricted to citizens (which usually meant free male landowners who possessed over a certain amount of wealth) to the exclusion of many other members of society, these assemblies provided the creative outlet for the development of politics and law. By being a citizen, a man was seen as possessing a kind of common interest in the good of the state. Unlike the modern man, who believes in communal responsibilities and individual rights, the Greeks and Romans believed in communal rights and individual responsibilities. Because it was a communion of citizens who formed the state, the citizen was entitled to certain benefits from the state, mainly through its legal advantages. The making of laws, judgment of courts and matters of war were all left up to the discretion of the citizen body. When the citizens came together in the assembly, their authority was supreme and their word was law.

Unlike in the east, the assembly did not receive this authority from the gods, but from the people. But the gods did have a role to play as a kind of supernatural legal “witness” to the laws enacted by the assemblies. New legislation was often proclaimed in the local temple (such as the temple of Jupiter Capitolinus in Rome) and accompanied by sacrifices. This represented a kind of oath between the gods and the state; the state promised that its legislation would be fair and equitable to the citizens and the gods promised to uphold the state so long as they were propitiated by the appropriate rites and the practice of pietas-devotion to the gods, family and the state. This ensured the good faith (fides) of the magistrate and the pax deorum, which was the peace and blessing of the gods upon the state.26

Essentially, like much in the Greco-Roman world, the relationship between the gods and the state was like a legal contract, akin to a Roman patron-client agreement.

To sum up the western model: First, the authority to rule came not from the gods but from the collective consensus of the people, not understood in terms of the masses but in terms of the land owning male citizenry. Secondly, the authority and will of the people was vested in any number of elected citizen assemblies who undertook the task of governing the state. Levying taxes, making laws, regulating trade and waging war were all public matters decided by the assemblies. Third, magistrates were chosen from out of these assemblies, in whom was vested authority by virtue of their office, not their person, as in the east. The Greeks and Romans possessed an innate valuation of certain virtues that they believed made for good magistrates, such as arête and virtus. Finally, the proper governing of the state under worthy magistrates ensured peace at home, good will between the state and its people (fides) and the blessings of the gods (pax deorum).

The Problem of Integration

Christian Europe would work hard to integrate its rich Greco-Roman past into its culture. While Biblical heroes such as David and Solomon were the exemplars for medieval Christian kings, classical role models of virtue like Leonidas of Sparta, Marcus Atilius Regulus, Cato the Censor and Augustus were never far from the memory of those who were educated enough to read the Greek and Latin classics.27 Christian monarchs tried, intentionally and unintentionally, to successfully blend the eastern Biblical ideology of kingship with the classical western models they had inherited from Greece and Rome. Thus Charlemagne was seen not only as a new David, but also as a new Augustus.

It took the creative impulse of Christianity to unite these two ideologies of power into one system. The ancients were never able to do it effectively. The ancient Greeks, though warring incessantly against themselves, united and battled furiously what they considered to be the threat of Persian despotism under Xerxes. Alexander, though he succeeded to unite Greece and Persia where Xerxes had failed, faced a considerably greater struggle in his attempts to jointly rule the Greeks and Persians. As ruler of Persia, court protocol demanded the prostration, proskynesis, of all who approached him. But as King of Macedonia, court protocol forbid such acts of flattery as the worst form of syncophancy and there was always tension between the Macedonian and Persian elements of Alexander’s entourage.28

In the Roman world, Marc Antony fancied a union between Rome and Egypt in the person of Cleopatra, but was despised at home for it. Anti-Antony propaganda of the time condemns him as an effeminate Egyptianizer of the manly Roman state.29 Later Roman rulers like Diocletian attempted to introduce eastern ritual into the Imperial court protocol, but at the expense of thoroughly destroying any remnants of Republican modesty that earlier emperors like Augustus, Vespasian and Trajan had exhibited. Throughout the ancient world, all attempts to find a way to implement both eastern and western ideas of power and government failed until the advent of the Catholic kings of the Middle Ages. How Christianity revolutionized the ideologies of power in the ancient world, harmonized them and formed them into the institution of the Christian monarchy will be taken up in the next chapter.

Footnotes

1 Jan Assman, The Mind of Egypt, Translated by Andrew Jenkins (Metropolitan Books: New York, 1996), 184

2 Jean Bottero, Religion in Ancient Mesopotamia, Translated by Teresa Lavander Fagan (University of Chicago Press: Chicago, 2001), 103

3 M.I. Finley, The Portable Greek Historians (Viking Penguin: New York, 1959), 97

4 Stuart & Doris Flexner, The Pessimist’s Guide to History (Avon Books: New York, 1992), 7

5Dan. 3:1-6, 6:6-9; Esther 4:11

6 Bottero, 114

7“Superior abilities, functions, prowess, and merits could, without affecting their true nature, place…humans rather close to the edge so that they were induced, more or less consciously, to cross over it, thus becoming ‘divinized.’” Ibid., 64

8 The Israelite “Law of the King” appears in Deuteronomy, where the king is forbidden three things: the multiplication of wives, gold, and chariots (Deut. 17:14-20). Solomon will violate all three precepts.

9 Deut. 17:15

10 I Sam. 8:7

11 Ibid., 16:1-13

12 Ibid., 10:1, 16:3

13 Ibid., 15:24

14 Ibid., 23,28

15 I Kings 11:11

16 Ibid. 3:1-15,26; 6:1-38; 10:1-29; 11:1-8

17 Prov. 16:10

18 Ecc. 10:20

19 II Kings 21:10-15; 23:26; 24:1-4

20 This is still true in ancient Israel, even though the kings had a stricter ethical code than say Assyria or Babylon. The value placed on the person of the king is revealed in the accounts of how David refused to strike down Saul, even when he had lost God’s favor, because he was “the Lord’s anointed” ( II Sam. 1:14). He even has the man who killed Saul executed (v. 15). This is similar to the accounts of Alexander executing the men who had assassinated Darius III, though the latter was his enemy. Since sacred authority rested with the king, it was a sacrilege to strike him down, even if he deserved it.

21Assman, 51

22 Ibid.

23 Michael Grant, History of Rome (Michael Grant Publications: London, 1979), 66

24 Thomas F.X. Noble, Barry S. Strauss, Duane J. Osheim, Kristen B. Neuschel, William B. Cohen, David D. Roberts, Western Civilization: The Continuing Experiment, 3rd Edition, vol. A (Houghton Mifflin Company: Boston, 2002), 73, 149

25 Ibid., 75

26 Grant, 19

27 St. Augustine spends a considerable amount of space in Book I of the Dei Civitas praising the virtues of M. Atilius Regulus, a hero of the Punic Wars, though grudgingly admitting that his virtue came from the worship of the pagan gods. He says of him, “Among all their heroes, men worthy of honor and renowned for virtue, the Romans have none greater to produce.” St. Augustine, Dei Civitas, 1.15,24

28 For the hostility of the Macedonians when Alexander attempted to introduce proskynesis amongst them, see Mary Renault, The Nature of Alexander (Pantheon Books: New York, 1975), 172-178: “The image of the Oriental was linked in [the Macedonians’] minds…to the cruel caprices of despotic power slavishly endured, of which the prostration [proskynesis] was a symbol.”pp 177-178

29Grant, 200-201